This week in Newly Reviewed, Yinka Elujoba covers Elmer Guevara’s delicate work, James Casebere’s reimagined structure and John Ahearn and Rigoberto Torres’s busts of Bronx residents.

Chinatown

Elmer Guevara

By way of Aug. 3. Lyles & King, 19 Henry Avenue, Manhattan; 646-484-5478, lylesandking.com.

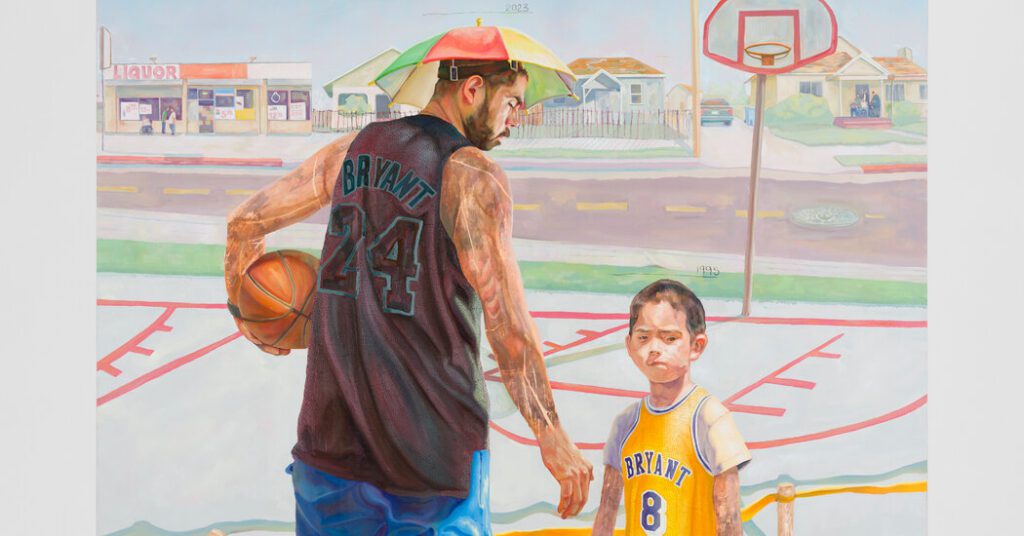

A person in an umbrella hat reaches right down to a boy by a basketball courtroom. Each put on “Bryant” jerseys. The neighborhood appears peaceable on a sunny day however at their toes are names and a chalk define of a human physique.

This scene, from Elmer Guevara’s “Hoova’ Park Stroll,” embodies the feelings of “Recess,” his first solo exhibition in New York.

Within the Eighties, Guevara’s dad and mom escaped to america from the brutal civil warin El Salvador. Stuffed with visible cues from his early years in South Central Los Angeles, the place he was born and nonetheless lives, the present is the artist’s reckoning together with his childhood. Actually, the 2 figures in “Hoova’ Park Stroll” are his self-portraits at completely different ages.

Utilizing extracts from household images, information clippings and movie stills, Guevara makes seen the native tradition of the immigrant melding into a brand new lifestyle. Maybe this notion of settlement is most palpable within the youngsters with their selfmade Halloween costumes and interesting array of sneakers: Theirs might be a future vastly completely different from their dad and mom’ previous.

Though the work are vibrant, the present’s power is in its subtleties. Beneath the veneer of peaceable and gradual dwelling lies the trauma and violence interwoven with the artist’s upbringing: Stashes of money recall his guardian’s mistrust of banks. In “Ready for Dusk,” youngsters in Halloween costumes await the possibility to trick or deal with, surrounded by a black cat, a menacing coyote and the chalk define of a lifeless physique. The assertion “Recess” makes is obvious: Immigrants’ conditions are all the time precarious, whilst they discover new and stable floor.

Chelsea

James Casebere

By way of Aug. 2. Sean Kelly, 475 tenth Avenue, Manhattan; 212-239-1181; skny.com.

By photographing table-size fashions he makes of buildings, prizewinning architectural designs and historic reimaginings, James Casebere re-examines suburban, Indigenous-made and institutional buildings, whereas elevating questions on societal energy constructions. In “Seeds of Time,” his ninth solo present at Sean Kelly Gallery, the artist turns towards environmental sustainability.

Casebere, born in 1953, makes use of easy supplies for his reconstructions, a lot of that are primarily based on the work of well-known architects. (“Cavern With Skylights” and “Balconies and Stairs” in “Seeds of Time” draw from the work of the Indian architect Balkrishna Doshi; the biomorphic kinds in “Patio With Blue Sky” and “Faculty” are interpretations of the Burkinabé-German architect Francis Kéré).

The photographs are haunting, since they’re absent of individuals. In “Seeds of Time,” this absence is much more evocative as a result of the buildings are positioned in water. The viewer will possible ask, “How does one dwell right here?” The latest floods in prosperous cities like Dubai, within the United Arab Emirates, nonetheless, show that there’s nothing unreal in regards to the prospects in Casebere’s pictures.

His vary of images additionally raises the query of how individuals from much less prosperous communities may survive environmental disasters. The floods in Dubai brought on the town to plan an $8 billion storm water runoff system. Evaluate this response to the individuals of Makoko alongside the coast in Lagos, Nigeria, which, in 2013, acquired the present of an revolutionary floating college from an architectural agency. The information drew consideration to Makoko, however the college was not often used and in the end wrecked by heavy rain in 2016. Casebere’s world has extra equality although, as his footage, whether or not primarily based on low-cost housing or grander designs, are devoid of individuals, indicating that local weather change will do the identical factor to the wealthy and the poor.

Higher East Facet

John Ahearn and Rigoberto Torres

By way of Aug. 16. Salon 94, 3 East 89th Avenue, Manhattan; 212-979-0001; salon94.com.

In 1979, the artists John Ahearn and Rigoberto Torres created 21 busts at Vogue Moda, a high-energy various artwork area that ran within the Bronx from 1978 to 1993. Often called “The South Bronx Corridor of Fame,” this group of portraits are actually, along with different sculptures, the topic of a brand new exhibition, “Walton Ave & Mates,” at Salon 94.

By the point Ahearn and Torres met at Vogue Moda, it had change into host to off-the-curve collaborations between the graffiti and hip-hop worlds. (Ahearn was born in Binghamton, N.Y., and settled within the Bronx; Torres was born in Aguadilla, Puerto Rico, and grew up within the Bronx.)

They weren’t conventionally educated artists. Torres realized mold-making and casting at his uncle’s manufacturing unit, which manufactured non secular figures, and Ahearn first found casting from a e book on make-up for tv and movie. However they adopted Vogue Moda’s observe of participating the area people, using residents as sitters. Proper on the sidewalk, they’d cowl a keen mannequin in plaster, and afterward the volunteer would obtain a painted copy of their sculpted portrait. It was a radical method to artwork, proving that nice work may very well be made outdoors the solitary air of a studio.

At Salon 94, the sculptures, principally leaning in opposition to or fastened to the partitions of the gallery, carry the infectious pleasure of any strange day in an everyday neighborhood. “Maggie and Connie” incorporates a lady getting back from grocery buying, her daughter holding on to her arm. In “Ralph and Kido,” a person performs with a younger boy; and a girl types a lady’s hair in “Carmen Combing Erica’s Hair.” The busts, set in an upscale ballroom with limestone partitions, are hung far above the heads of onlookers, in the identical means they have been displayed at Vogue Moda in 1979.

Ahearn and Torres produced these sculptures in an age when the South Bronx was devastated by crime and poverty. However the happiness in “Walton Ave & Mates” is how that age might be remembered, proving {that a} individuals’s triumphant legacy may be made attainable by means of communal participation in artwork making.

Final Likelihood

Life Cycles: The Supplies of Modern Design

By way of July 7. Museum of Trendy Artwork, 11 West 53rd Avenue, Manhattan; 212-708-9400, moma.org.

My favourite clock of all time is a video: A digital camera appears down onto two skinny mounds of rubbish, perhaps 20 and 15 toes lengthy, assembly at one finish just like the hour and minute arms on a watchface; for the 12 hours of the video, we see two males with brooms sweeping these “arms” into ever new positions, at a tempo that retains time.

The piece is by the Dutch designer Maarten Baas, and it’s among the many 80 works in “Life Cycles: The Supplies of Modern Design,” a gaggle present now in MoMA’s street-level gallery, which has free admission.

The “supplies” of in the present day’s most compelling design transform concepts, even ethics, not the chrome or bent wooden that MoMA’s title would as soon as have invoked. This present’s moral concepts middle on the setting and the way we’d handle to not abuse it.

Baas’s “Sweeper’s Clock,” is completely practical — might I view it on an Apple Watch? — nevertheless it additionally works as a meditation on the Sisyphean, 24/7 job of coping with the trash we generate.

All-black dishes by Kosuke Araki look very just like the minimalist “black basalt” china designed by Josiah Wedgwood means again in 1768 (it’s a few of the oldest “modernism” claimed by MoMA) besides that Araki’s variations are made with carbonized meals waste.

Meals under no circumstances wasted, however consumed — by cattle — goes into making Adhi Nugraha’s lamps and audio system, as defined by the title of the sequence they’re from: “Cow Dung.” BLAKE GOPNIK

Higher Manhattan

The Phrase-Shimmering Sea: Diego Velázquez / Enrique Martínez Celaya

By way of July 14. The Hispanic Society Museum & Library, 613 West a hundred and fifty fifth Avenue, Manhattan; 212-926-2234, hispanicsociety.org.

There are locations you may’t simply return to, like childhood or, for a lot of migrants and refugees, the nation the place they have been born. This was true for Enrique Martínez Celaya, who was born in Cuba and relocated together with his household to Madrid when he was a younger boy. Martínez Celaya, now nearly 60, returned to Cuba solely in 2019, however he has discovered a means of retrieving each childhood and homeland on this spectacular exhibition on the Hispanic Society.

Massive canvases by Martínez Celaya embrace blown-up snippets from his childhood pocket book, surrounded by interpretations of waves and seascapes. In a stroke of kismet, the pocket book from which these early drawings have been copied was given to him by his mom and featured a copy of a portray on its cowl: Diego Velázquez’s “Portrait of a Little Woman” circa 1638-42, which is within the assortment of the Hispanic Society. That portray is displayed at one finish of the room.

Objects and their historic hierarchies are irreverently jumbled within the present: Velázquez, the nice Spanish painter, sits alongside Martínez Celaya’s infantile doodles. In one other sequence of work by Martínez Celaya, the “Little Woman” holds objects that he coveted as a boy. The exhibition additionally contains work by different artists, just like the 1971 pocket book of Emilio Sánchez, an artist born in Cuba in 1921 who by no means went again to his homeland after 1960. In the long run, the topic of the exhibition is admittedly an immaterial poetic thread during which reminiscence is fleeting however artwork, in its varied kinds, connects individuals, locations and historical past. MARTHA SCHWENDENER

Extra to See

Higher East Facet

Jutta Koether: 1982, 1983, 1984

By way of July 27. Galerie Buchholz, 17 East 82nd Avenue, Manhattan; 212-328-7885, galeriebuchholz.de

“What would you like,” Jutta Koether wrote in 1984 in regards to the band the Cramps on the event of its raucous, triumphant debut in Paris, “intercourse, enjoyable, hysteria, a racket from battered amplifiers and abused guitars, sweaty our bodies, dust, sleazy chords and the sensation {that a} storage continues to be the perfect place for music?”

Koether’s writings, which appeared within the German pop-culture journal SPEX within the Eighties, are well-known for her good, powerful takes on artwork and music. If you weren’t lucky sufficient to get your arms on a duplicate of the unique print editions, in German, you’ll have the possibility in “Jutta Koether: 1982, 1983, 1984” at Galerie Buchholz. The exhibition features a binder of her writings, translated into English, in addition to her earliest, darkish expressionist work.

The work and writings are of a chunk. “Asserting the wedding of existentialist black shades with the spiked leather-based collar of rock ’n’ roll,” she wrote in 1984. “To have a good time, Sonic Youth has launched a brand new EP.” The canvases have an analogous spiked, existentialist swagger. The palettes are moody and the surfaces are stubbly. Some works listed here are summary, others function gaunt, alien faces, surrealistic shapes or a pair of limbs wrapped for battle, which seems to be a feminine boxer.

However there’s additionally a way of nostalgia. The bands written about are gone, and lots of the performers, like Nico and Lou Reed, are not with us. Equally, Koether’s work really feel very a lot from one other time, which may very well be the 1910s or the Nineteen Twenties — the unique period of disaffected German expressionism — or the gritty Eighties. Nonetheless, battered amplifiers, sleazy chords and a storage to play them in are nonetheless nice fashions for music, and artwork. MARTHA SCHWENDENER

Chelsea

Ina Archer

By way of July 27. Microscope Gallery, 525 West twenty ninth Avenue, Manhattan; 347-925-1433, microscopegallery.com

“To Deceive the Eye,” a present by the experimental filmmaker and artist Ina Archer, hinges round a 1933 Bing Crosby movie, “Too A lot Concord,” that incorporates a track titled “Black Moonlight.” In that musical quantity, white refrain women morph into Black performers by means of the usage of particular results — a type of technological blackface.

Archer’s 2024 video set up, “Black Black Moonlight: A Minstrel Present,” contains footage from “Too A lot Concord” and different minstrel performances. The photographs are organized with clips from James Baldwin’s well-known 1965 debate with William F. Buckley Jr. in regards to the American dream. Moreover, the partitions are lined with Archer’s watercolors of dolls and collectible figurines, some racially charged, and a brief 16-millimeter movie, “Trompe l’oeil: Black Chief” (2023), that options coloration charts and model heads that allude to the issue of capturing darkish pores and skin on celluloid movie.

Different Black artists, like Adrian Piper and Arthur Jafa, have made works extracted from Hollywood archives. What Archer brings is a canny sense of the bewitching potential of celluloid. Manipulating the archive into an artwork object, she seduces you into watching — and observing — the appalling methods racism has manifested in cinema. MARTHA SCHWENDENER

Tribeca

Susan Weil

By way of July 26. JDJ, 370 Broadway, Manhattan; 212-220-0611, jdj.world

Susan Weil is lodged firmly in artwork historical past, however in an auxiliary means. After attending the famed Black Mountain artwork college in North Carolina within the Nineteen Forties, she married Robert Rauschenberg and the 2 made a sequence, “Blueprints” (1949-1951), by capturing human our bodies on light-sensitive paper. The body-silhouette concept has been explored by many artists, together with David Hammons and Keltie Ferris, however Weil stays a lesser-known determine. Now 94 years outdated, she continues to be portray and writing poetry, and you may see 50 years of her work at JDJ in Decrease Manhattan.

These works, from 1969 to 2023, present a persistently intelligent method to representing the physique in two dimensions. A number of pastel “Spray Drawings” from the early Seventies appears at first like geometric abstractions, till you notice that you just’re seeing the outlines of legs and arms and torsos. “Strolling Determine” (1968), made with spray paint on plexiglass, revamps the Nineteenth-century photographer Eadweard Muybridge’s “human locomotion” experiments. Different works method landscapes in a wildly ingenious means, like “Gentle Panorama” (1972), with its horizontal bands of earth and sky painted on canvas that has been draped from the wall like a jacket held on a peg.

Current works use opalescent or iridescent interference paint that causes the picture to shift when seen from completely different angles. Right here, Weil tracks phases of the moon or the trajectory of the solar. All through, the frequent thread is a mild, playful means of observing our bodies, planets and the act of artwork making. MARTHA SCHWENDENER

Chinatown

Pat Oleszko

By way of July 20. David Peter Francis, 35 East Broadway, No. 3F, Manhattan; 646-669-7064; davidpeterfrancis.com.

Pat Oleszko has carried out at MoMA, the Whitney, P.S. 1 and P.S. 122, however “Pat’s Imperfect Current Tense,” at David Peter Francis in Chinatown, is her first solo present in practically 25 years. As you’d anticipate, it’s overflowing with 5 a long time’ price of hats, costumes, indicators and movies that enjoyment of subversion and take subversively uncomplicated pleasure in delight.

In “Footsi,” two fingers in tiny footwear and socks tiptoe throughout a girl’s bare stomach. In “The place Fools Russian,” Oleszko takes purpose at Chilly Battle paranoia, “Dr. Strangelove” fashion, by placing on a dozen layers of clothes and submerging herself within the Atlantic. There’s an infinite inflatable pelvis by means of which she can provide delivery to herself (“Womb With a View”), a “coat of arms” made for the fiftieth anniversary of the Surrealist Manifesto and an analogous however extra revealing “handmaiden” costume designed for a striptease in Japan. The punning is relentless.

There’s a transparent feminist chew to a lot of this, and a frequent political edge that ranges from pointed to broad. There’s even a lightweight tweaking of art-world classes, because you’re by no means fairly positive if these are sculptures masquerading as costumes or vice versa. However the true subversion right here is solely Oleszko’s full-scale refusal to take herself, or the rest, significantly: It’s onerous to take part in this sort of humor, whilst a viewer, with out shedding maintain of no matter severe, oppressive journey you might have walked in with. WILL HEINRICH

TriBeCa

‘Threads to the South’

By way of July 27. Institute for Research on Latin American Artwork (ISLAA), 142 Franklin Avenue, Manhattan; islaa.org.

For many years, textile artwork was trivialized as “craft” and “girls’s work” by mainstream U.S. establishments. That longstanding bias has began to erode, however numerous fiber artwork practices stay underexplored. “Threads to the South,” an exciting exhibition curated by Anna Burckhardt Pérez, spotlights a few of them.

The present focuses on Latin America, a area with lengthy and various thread-based traditions. Most of the 22 artists from 10 nations draw on these heritages, together with Julieth Morales, a member of Colombia’s Misak Indigenous neighborhood. Her piece “Untitled” (2022) is woven within the fashion of a striped Misak skirt, however hangs as a substitute as an unfinished banner from the ceiling — an announcement of delight and chance.

The exhibition is intergenerational, however the knockouts are principally older. Amongst them are Olga de Amaral’s “Tapete — Número 330” (1979), a checkered wool and woven leather-based rug; Nora Correas’s “En Carne Viva” (1981), an animalistic bundle of darkish crimson and fuchsia wool kinds; Jorge Eielson’s “Amazonia XXVII” (1979), a cross between historic Andean and Western postmodernist traditions; and Feliciano Centurión’s embroideries on artificial blankets from the Nineties. These disparate works are alternately visceral and cerebral, intimate and stylish. They increase the canon and customary understanding of fiber artwork and who makes it.

Themes emerge all through the present, however in the end “Threads to the South” is about identification. Not in a reductive means, as has typically been the case within the U.S. Fairly, the exhibition argues convincingly that as a result of cloth is on the root of a lot Latin American artwork and life, it deserves, even calls for, to maneuver from the margins to the middle. JILLIAN STEINHAUER

‘Portray Deconstructed’

By way of Aug. 18. Ortega y Gasset Initiatives, 363 Third Avenue, Brooklyn; oygprojects.com.

What makes a portray a portray? Is it the applying of coloration to canvas or board? The truth that it hangs on a wall? What about various kinds of artwork which are knowledgeable by portray’s histories and conventions? The place ought to we draw the road (pun supposed)?

These are a few of the questions raised by “Portray Deconstructed,” an exhibition that includes 46 up to date artists who work in a variety of mediums and supplies. That’s what makes the present equally good and enjoyable: You gained’t discover a simple portray wherever. As an alternative you’ll discover items made from ceramics, cloth, pictures, and even balloons that evoke work, and paint utilized to all method of surfaces, together with T-shirts and palm husk.

For me, wanting forwards and backwards between the artworks and guidelines turned a type of treasure hunt. I needed to seek out out what components made up Scott Vander Veen’s splendidly tactile “Graft #2 (Thigmomorphogenesis)” (2023). Studying that Jodi Hays used a discovered plein-air portray equipment in her weathered “Self Portrait at 61” (2024) made me chuckle.

Kevin Umaña’s “Cut up Apple Core” (2023) is a technical marvel: a posh and luxurious ceramic work that may very well be an summary portray. I delighted within the conceptual cleverness of Erika Ranee’s multimedia and nonrepresentational “Selfie” (2024), which incorporates black-eyed peas, a plant and the artist’s hair dipped in acrylic.

There’s exceptional talent on view all through “Portray Deconstructed,” nevertheless it doesn’t really feel prefer it’s being deployed solely for technical ends. These artists experiment with a view to open up the class of portray. They use what it has been to think about what it’d but be. JILLIAN STEINHAUER

Monetary District

Christopher Wool

By way of July 31. 101 Greenwich Avenue (entrance on Rector Avenue), Manhattan; seestoprun.com.

The dilapidated Nineteenth-floor workplace area internet hosting Christopher Wool’s latest sculptures and work couldn’t be extra simpatico with them. In its state of deserted tear-down, the venue gives melodious visible rhymes: electrical cords dangling from the ceiling ape Wool’s snarls of found-wire sculpture; crumbling plaster mirrors the attitudinal blotches of his oils and inks. Scrawls of crude graffiti or shortly penciled notes left by workmen emulate the tendril-like traces dragged by means of Wool’s globular plenty of spray paint. The area is a horseshoe-shaped echo of Wool’s work — uncooked, agitated — and the stressed class he wrenches from a sense of decay.

Wool stated he began to consider how setting impacts the expertise of taking a look at artwork when he started splitting his time between New York and Marfa, in West Texas. Photographic sequence he made there, like “Westtexaspsychosculpture,” depict forlorn whorls of fencing-wire particles that seem like uncanny mimics of Wool’s personal writhing scribbles, and which impressed scaled-up variations forged in bronze. (The Marfa panorama is fertile floor for New York artists. Rauschenberg made his scrap steel assemblages after witnessing the oil-ruined panorama of Eighties Texas, what he referred to as “souvenirs with out nostalgia,” a designation that’s applicable right here, too.)

Place has all the time seeped into Wool’s work. His images of the grime and trash-strewn streets of the Decrease East Facet within the Nineties — compiled as “East Broadway Breakdown” — aren’t included right here, however “Incident on ninth Avenue” (1997), of his personal burned-out studio, are. The chaos of these scenes repeat right here, the wraparound ground plan and limitless home windows letting the town permeate the work, simply because it did of their making. MAX LAKIN

SoHo

Robert Irwin

By way of Aug 31. Judd Basis, 101 Spring Avenue, Manhattan; 212-219-2747, juddfoundation.org. Public hours: Friday–Saturday, 1:00–5 p.m., or by appointment.

In 1971 Robert Irwin put in a 12-foot acrylic column within the floor ground of Donald Judd’s SoHo studio, a prism positioned to select up mild from the constructing’s massive southern and western home windows. Because the early ’60s, Irwin had been pushing the definition of artwork past objecthood, steadily lowering his work of distractions till he stopped producing salable artwork works. By 1970, he had deserted his studio in favor of what he referred to as a conditional observe: making delicate, barely perceptible interventions in structure to tease out the marvels of visible potential. He seen his installations merely as instruments to induce the true artwork, which was notion — “to make individuals aware of their consciousness.”

A later iteration of that work, “Sculpture/Configuration 2T/3L,” first exhibited at Tempo in 2018, is on view in roughly the identical spot (the outlet bored by means of the ground 53 years in the past stays, by no means crammed). Extra superior, shaped by two columns of stuttering panels of teal and smoky brown acrylic, it’s lovely, however its magnificence is irrelevant. It melts into the background, each there and never there. Daylight catches a nook or flutters over a faceted edge as you progress round it, splicing and refracting SoHo’s thrum, making it new.

The set up’s future means the standard of pure mild will change and so too will the impact. It’s a gradual, affecting distillation of Irwin’s philosophy, which stays generously contra the artwork world’s relentless demand for novelty. Irwin, who died final yr, refined an expansive imaginative and prescient, making us conscious of the transitory, letting us see what was all the time there, for so long as we are able to. MAX LAKIN

Chelsea

Huong Dodinh

By way of Aug. 16. Tempo Gallery, 540 West twenty fifth Avenue, Manhattan; 212-421-3292; pacegallery.com.

Buoyed by a terrific sense of calm, and even silence, the work in Huong Dodinh’s “Transcendence” signify an artist’s triumph after a long time of pursuing concision by adopting a minimalist vocabulary. It’s this Paris-based artist’s first-ever solo exhibition in america in her near 60 years of portray.

Starting with a uncommon 1966 figurative portray, whose colours appear to recall Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s “Hunters within the Snow,” the present progresses to the ’90s and to the final couple of years. Figuration falls away because the a long time move, the artist’s hand turns into much less pronounced, and by the 2000s Dodinh’s central issues emerge: mild, density, transparency and the way these work together with traces, kinds and area. These come collectively gracefully in works like “Sans Titre,” from 1990, during which three sensual curves depict what may very well be mountains in a desert, or layers of ladies’s breasts.

Dodinh’s mushy palette — a quiet however delightsome vary of carton browns, mild blues, and off-whites — originated from her first expertise with snow in Paris, the place her household fled from Vietnam in 1953 throughout the First Indochina Battle. She was a toddler in boarding college when she first witnessed snow and marveled at the way it revealed delicate colours beneath when it began to soften. Subtlety, a trademark of Dodinh’s work, is one thing she goes to nice lengths to realize: She has all the time labored alone, with out assistants, makes her personal pigments, guaranteeing that each inch of her canvas is stuffed with an power that’s wholly hers. It has been an extended solitary journey and in any case these years, even whereas Dodinh masters the artwork of austerity, her work feels adorned. YINKA ELUJOBA

East Harlem

‘Byzantine Bembé: New York by Manny Vega’

By way of Dec. 8. Museum of the Metropolis of New York, 1220 Fifth Avenue, Manhattan; 212-534-1672, mcny.org.

In celebration of its centennial yr, the Museum of the Metropolis of New York invited Manny Vega to be its first artist in residence. Fabulous selection. Vega is a local New Yorker and a treasure, with a virtually four-decade observe document of visible scintillation behind him. The essence of that profession is distilled in a 24-karat nugget of a survey, “Byzantine Bembé: New York by Manny Vega,” assembled by Monxo López, the museum’s curator of neighborhood histories.

Puerto Rican by descent, Vega was born in 1956 within the Bronx, raised there and in Manhattan, and an immersion in artwork got here early. One in every of his first jobs after graduating from the Excessive Faculty of Artwork and Design was as a guard on the Cloisters, the Met’s department in Higher Manhattan dedicated to European medieval artwork. In 1979 he joined El Taller Boricua (Puerto Rican Workshop), the street-active artist collective and graphics workshop within the East Harlem neighborhood often known as El Barrio.

Within the early Eighties, he started touring to Brazil, the place he was initiated into Candomblé, an Afro-Atlantic faith that fuses West African Yoruba and Roman Catholic beliefs and has a vivid custom of ceremonial artwork, together with beaded banners and ritual utensils, each of which Vega has produced. Given these entwined influences, typical distinctions between “excessive artwork,” “widespread artwork” and “religious artwork” have by no means made sense to him, which explains the title of his present, “Byzantine” suggesting intricate formal polish; and “Bembé” evoking drum-driven non secular worship that can be a celebration.

The combination is there in 4 small work he made in 1997 as research for a set of mosaics commissioned by the Metropolitan Transportation Authority for the subway station at East a hundred and tenth Avenue and Lexington Avenue. Brightly coloured and full of figures, the pictures depict El Barrio avenue life — neighbors jostling, distributors promoting, bands enjoying — and provides it a cost of devotional fervor, aural exultation. (A tour of different Vega commissions in East Harlem, all inside strolling distance of the museum, is properly price making, a spotlight being his tender homage to the poet Julia de Burgos (1914-1953) on a constructing at East 106th Avenue and Lexington Avenue.)

Sound and motion are main elements in Vega’s visible universe. Icon-like pictures of Ochun, the Yoruba goddess of dance, and St. Cecilia, the Roman Catholic patron saint of music, seem within the present as tutelary spirits. And there are others. One is the Barrio-born jazz musician Tito Puente, whose album covers Vega has reproduced as glass mosaics. And in a big ink drawing, as crisp as a woodcut, we discover the assembled performers of Los Pleneros de la 21, an area dance and music troupe selling conventional bomba and plena.

Politics runs, like a bass notice, all through Vega’s artwork. In his case, although, it’s far much less a politics of overt protest than of optimistic assertion.

Within the work of this profoundly devotional artist, the presiding deity is Changó, the Afro-Atlantic spirit of justice and stability, and likewise of dancing and drumming. A watercolor portray of him closes the present, and it’s a traditional Vega creation: formally exact, imaginatively stimulating, immediately accessible. And it has discovered simply the correct dwelling. It’s on mortgage to the present from Supreme Court docket Justice Sonia Sotomayor who, a wall textual content tells us, shows it in her chambers in Washington. HOLLAND COTTER

See the June gallery exhibits right here.